Motherhood realness in 1850s Iowa

I will give you the “youngest” for a birthday present if you will come for her. “I’m not joking,” I get better very slowly.

So begins Sarah Underwood’s letter to her sister Ann two weeks after giving birth to Mary Lillian Underwood. Sarah was 30 years old and had been living in Iowa for about three years after she and her husband, Horace, left Kingston, Rhode Island to take advantage of the farming opportunities afforded to white people by the removal of the Sauk and Fox in eastern Iowa and the forced cession of tribal lands. Princeton, where the Underwoods lived in Iowa, was ceded to the United States by the treaty known as the Black Hawk Purchase in 1833.

At the time the Underwoods lived in Iowa, it was considered the “West” by East Coasters. The Kingston area had a population of nearly 8,000 compared to Princeton’s population of around 450. To Sarah, Iowa seemed pretty, but sparsely populated and lonely. Her letters are full of her sense of isolation. Her longing for her family and friends in Rhode Island is palpable. Her days seem to have been full of housework, cooking, hosting farm laborers, sewing, gardening, picking flowers, and wandering the prairies near her home. Her mind seems to have been occupied by the social life that was lacking in her new environs. She often asked her sisters for news of “beaus,” and kept a collection of daguerrotypes that she would show visitors to her home in Iowa. In a time before color photography, she kept abreast of East Coast fashions and the new drapery in the family home through snippets of fabric her sisters sent to her by mail. In return, she helped her sisters get a sense of what Sarah saw by mailing them pressed flowers and leaves.

When Lillian was born, Sarah again relied on the mail to paint a picture of the newest family member by honestly relating her feelings as a woman who recently became a mother.

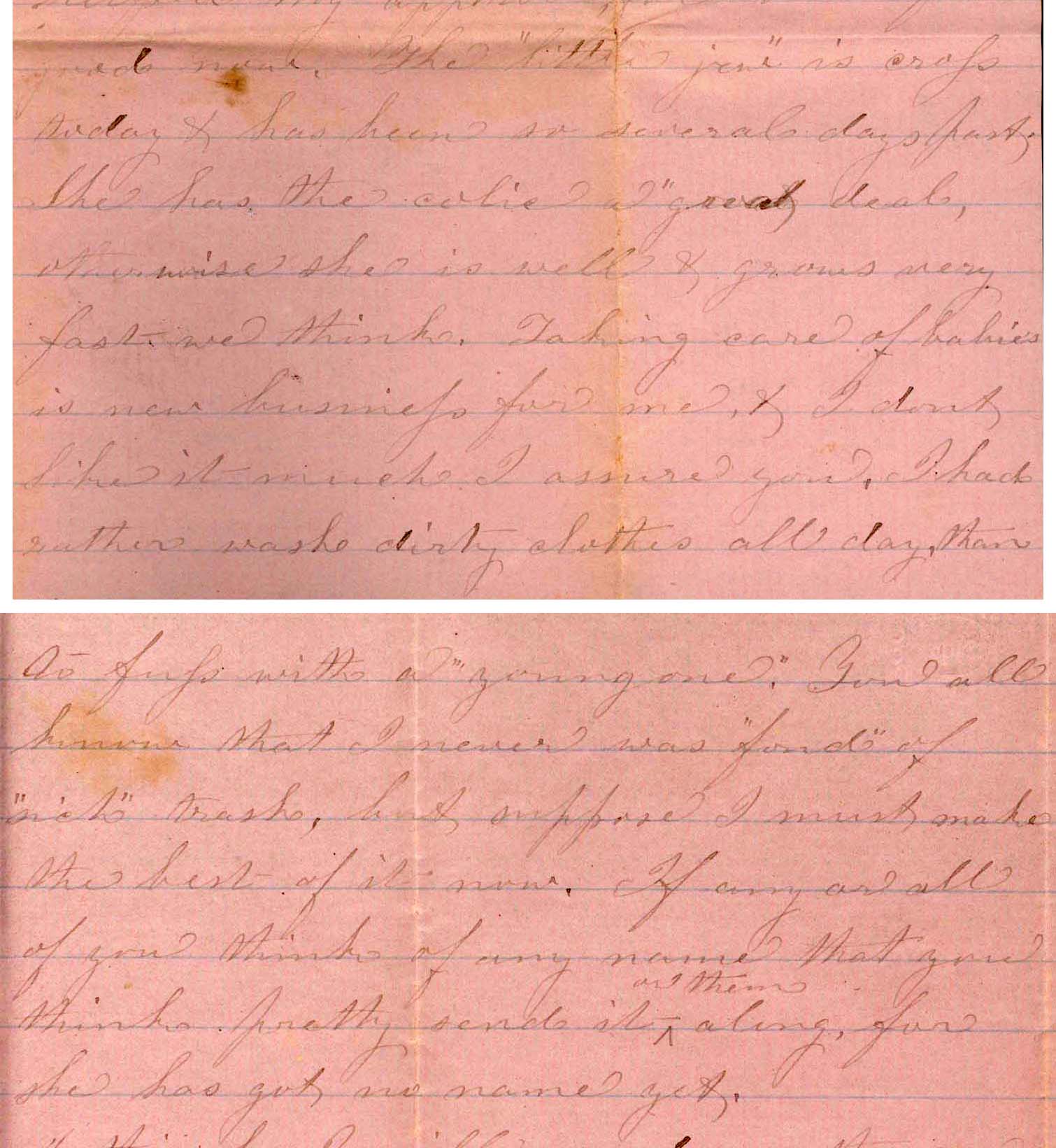

Letter from S. U. to “Dear Sister,” November 8, 1859 (MS 694, Box 1, Folder 10)

The “little one” is cross today & has been so several days past. She has the colic a great deal, otherwise she is well & grows very fast we think. Taking care of babies is new business for me, & I don’t like it much I assure you. I had rather wash dirty clothes all day, than as fuss with a “young one.” You all know that I never was “fond” of “sick” [trash?], but suppose I must make the best of it now. If any or all of you think of any name that you think pretty send it or them along, for she has got no name yet.

Despite the intimacy and frankness of Sarah’s letters to her sisters, missing from the collection is any correspondence announcing her pregnancy, so we have no idea of how Sarah talked about her pregnancy or her thoughts on the child-to-be. These letters are particularly noteworthy in that they reveal, directly, a counterpoint to the “cult of true womanhood” that was prevalent at the time. Rather than finding motherhood fulfilling and the outcome of her “natural” place in the world, Sarah seems comfortable expressing that she finds the immediate aftermath of Lillian’s arrival decidedly unpleasant.

By spring of the following year, Sarah seems to have made some peace with her new role. She begins recounting stories of Lillian in her letters, even folding Lillian in to the clothing discussions she had with her sisters:

She has five white dresses now, & a dress made of that yellow & white apron that Mae gave me that summer I was at home, I guess she will remember. – Letter from Sadie to her “Sister Dear” March 18, 1860.

Sarah’s letters are a remarkable insight into one woman’s experience of, and reflection on, motherhood, adaptation, and isolation. We’ve scanned the entire set of letters from the archives collection and will be be launching the digital version very soon.